Victor Paterno and his allies seek to rollout and fund community-based drug rehab like a new business

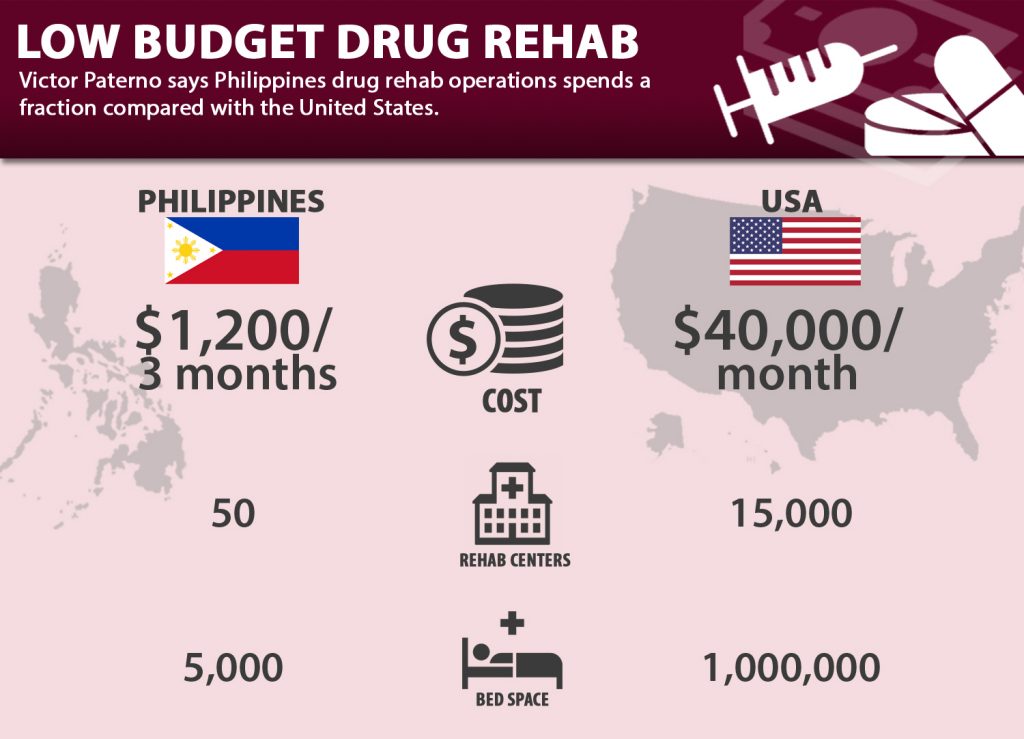

7-Eleven Philippines chief Victor Paterno pitched not one but two ambitious plans when he addressed the Makati Business Club in March. The first is a plan to roll out community-based drug rehabilitation programs, working with police and local leaders to curb drug-related deaths by getting communities certified as drug-free zones.

The second is a proposal to finance the plan in start-up fashion, with investors coming in at several phases in venture-capital style.

Paterno is a leader of the Bishops-Businessmen’s Conference, which assigned him to lead its community-based drug rehabilitation program. He says maybe because of his experience with taking a business model and planting it around the country. (7-11 has 2,287outlets in the Philippines)

Over 18 months, he’s become part of an alliance of police officers, priests, Ateneo’s Center for Family Ministries (CEFAM), and RAPID, a Seaoil-funded drug rehab NGO whose members include a police chief and whose head, maybe not coincidentally, is the wife of the Cebu police provincial commander. They had great expectations for their Lost Sheep Initiative until they had to implement it.

“As any start-up will tell you, things that look full of promise on paper get their harsh dose of reality when they hit the ground. We hoped the Lost Sheep Initiative would scale rapidly and virally. The name and logo was created in hopes of attracting hordes of millennial volunteers on social media, whom we could match with parishes deluged with patients. We would compensate for the lack of trained facilitators with online videos and training provided by our partner CEFAM,” Victor Paterno said at the Makati Business Club meeting last March 19, 2018 at the Tower Club.

“In the end, there was a lot of political noise, and neither funding nor volunteers was easy to come by. So we pivoted to a more modest short-term goal of supporting existing efforts,” he said.

After some trial and error, Paterno says he is pushing to pilot in Metro Manila before a national roll-out. In his model, churches and local governments are providing the seed capital, private investors will fund the angel investor round, corporate foundations will enter in Series A, and foreign organizations in Series B.

The seed round was “very high risk, and we are in debt to the brave individuals and institutions that participated,” Paterno said. According to him, drug-related deaths fell 70 percent in areas with community-based rehabilitation programs.

The start-up is somewhere between seed capital and the angel round. Paterno says his group has P10 million of the P20 million they need to put 1,000 to 3,000 drug dependents through three- to six-month programs in at least 10 NCR cities and municipalities, or approximately 100 to 300 dependents per city.

“Malabon and Pateros have already submitted applications,” Paterno said.

If the numbers seem small, it’s because it is a proving ground for the next stage, where he is aiming for 10 times the money, this time from foundations, to take it national. They will “focus on improving documentation to a level acceptable to corporate foundations,” he said.

Not that there aren’t community-based rehabilitation programs around the country already. In fact, Paterno spoke alongside Superintendent Byron Allatog, police chief in Bogo City, Cebu. Allatog was a “star,” Paterno said, “with a story that gave everyone hope that this war could be won with less bloodshed.”

Allatog recalled going to every barangay in Bogo to get people behind what he calls his “whole-of-community” approach. He said he told one group after another that the drug war is not just a matter for the police but for every barangay captain and all the members of the community.

Allatog said he told them that they all had to acknowledge there was a problem, and that everyone should help fix it.

“It is a shared responsibility, sharing and sacrificing time and resources because it is our moral obligation and responsibility to protect our town because my family lives here, I work here, and my children study in this community,” Allatog said he told Bogo residents.

For winning the war on drugs with zero deaths in Bogo, Allatog has won local and international media attention— and a 2017 Ten Outstanding Young Men award.

Allatog pointed out that assuming the 624 former drug users that have graduated from the city’s drug rehabilitation program were consuming even just P300 worth of drugs a week, their rehabilitation meant stopping the flow of P8,985,600 per year to the illegal drug trade. If Bogo’s efforts were to be replicated and 10 surrenderees were to be saved in each of the 1,635 cities and municipalities throughout the country, that could conceivably result in an over-P200 million money denied off drug offenders.

If, as Paterno says, many start-ups end up doing something other than they had planned, he also bows to the fact that most start-ups fail.

“I probably don’t have to tell you there’s no IPO, because there’s no payback, at least in this life,” he said. “We would like to invite you to share in the credit if we succeed, and hopefully there will be enough of us to share the blame if things do not go as hoped.” (END)