Digital Democracy Handbook

Digital Democracy in the Middle of the Pandemic

Lessons from 5 Pilot Projects

Book 4

Embedding Digital Practices in the LGU

Table of Contents

1. Executive Summary

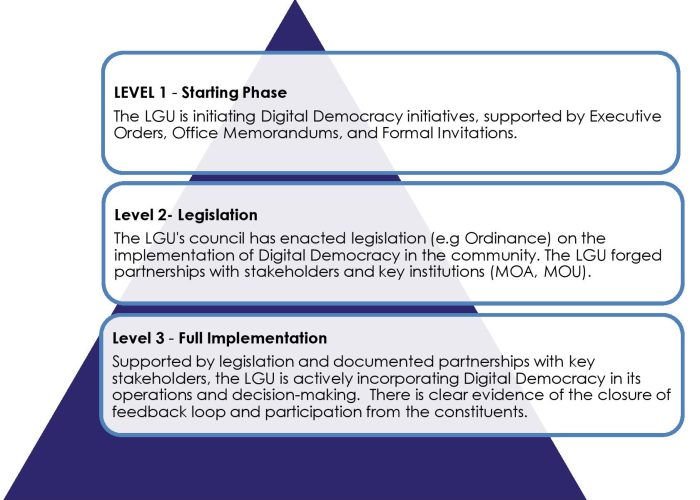

Embedding Digital practices in the Local Government improves the way we communicate with citizens, and encourages good governance. There are three levels of Institutionalization of Digital Democracy practices in an LGU:

Level 1 – Starting Phase

The LGU is initiating Digital Democracy initiatives, supported by Executive Orders, Office Memorandums, and Formal Invitations.

Level 2- Legislation

The LGU’s council has enacted legislation (e.g Ordinance) on the implementation of Digital Democracy in the community. The LGU has inked partnerships with stakeholders and key institutions (MOA, MOU).

Level 3 – Full Implementation

Supported by legislation and documented partnerships with key stakeholders, the LGU is actively incorporating Digital Democracy in its operations and decision-making. There is clear evidence of the closure of feedback loop and participation from the constituents.

To ensure best implementation of Digital Democracy in a local government or a regional government office, we recommend assigning a Digital Democracy Officer to coordinate and conduct e-consultations, data analysis, and presentation of the results of the LGU/NGA’s Digital Democracy initiatives. The DDO also ensures integration of overlapping issues such as gender and diversity. The DDO may also act as the focal point on technical and thematic issues, and perform tasks related to Digital Democracy initiatives.

2. Scope and Delimitation

This material serves as a general guide designed for all actors at all levels of the implementation of a Digital Democracy initiative and could provide an overview of the diverse opportunities to start Digital Democracy activities in their respective offices.

This material does not attempt to address all possible procedures or methods of Digital Democracy or imply that it is limited to the contents of this material. Readers are urged to view this handbook as an initial guide; to supplement their knowledge on the possible uses of ICT tools, procedures, and methods to enhance democratic processes, and inform decision-making and policy-making at the local government level. Finally, this material is not meant to replace domestic policies and procedures.

3. Introduction

The Digital Democracy Project helps local governments use online platforms to gather citizens’ thoughts. Embedding this practice into the LGU’s decision-making process would benefit both the government in making decisions informed by popular support, and increase civic participation in the democratic process.

Different LGUs have different key concerns and economic priorities. It is crucial that LGUs have their own policy-backed (e.g. Enabling Executive Orders, Ordinances, etc.) Digital Democracy initiatives to ensure that their activities are fit to their unique needs, key concerns, and community priorities. Furthermore, this removes the LGUs reliance on external organizations when conducting online consultations. This gives the LGUs control on the process and timelines.

This book serves as an initial guide to LGUs officials who want to regularly use digital tools to listen to their citizens, and embed this practice in their decision-making process.

4. Digital Democracy Officer (DDO)

To ensure best implementation of Digital Democracy in a local government or a regional government office, it is recommended to assign a Digital Democracy Officer to coordinate and conduct e-consultations, data analysis, and presentation of the results of the LGU/NGA’s Digital Democracy initiatives. The DDO also ensures integration of overlapping issues such as gender and diversity into the consultation. The DDO may also act as the focal point on technical and thematic issues, and perform specific tasks such as:

- Coordinating with civil society partners and stakeholders

- Performing research, data collection, and analysis about existing methodologies

- Reviewing, designing, implementing, and proposing new Digital Democracy projects

- Developing or delivering training using LGU’s developed methodologies and tools

- Performing communication tasks related to publication, and outreach of research and policy papers produced by the LGU;

- Monitoring compliance and ensuring quality delivery of project work plans and expenditure

Suggested skillsets of a DDO include:

- Digital Literacy – The DDO needs to be well-versed in using digital tools and platforms, to effectively coordinate with stakeholders and partners.

- Citizen Engagement – Digital Democracy projects are people-centric. It is important that the DDO can effectively engage communities and stakeholders.

- Research and Analysis – While technical data analytics can be outsourced to an external partner, the DDO should be able to understand how the insights were generated and how they can be translated to actionable suggestions for the LGU.

- Thematic Expertise – Some LGUs have their own economic priorities, key issues and concerns. If the consultation is frequently centered on a specific theme (e.g. Disaster Resilience, Tourism, etc.), a DDO with thematic expertise may be advantageous.

Ideally, the DDO is a plantilla position. This would ensure that the DDO thoroughly understands how the LGU works, and can effectively coordinate with the key persons involved. Choosing a DDO would really depend on the workload of the staff and the frequency of conducting Digital Democracy activities in the LGU. The workload of an LGU’s DDO with very active and cooperative stakeholders may be lighter than DDOs in other LGUs. In some cases, an FOI officer may also be the DDO. However, if the FOI officer’s existing workload is not ideal for a DDO appointment, the LGU can choose another staff for the role.

The salary grade of a permanent staff in the LGU with the above skillsets typically starts with SG 11.

For more information about the salary grades and compensation, here are sample documents from the Department of Budget and Management:

5. Budget and Resources

Digital Democracy initiatives require the use of resources, either from the LGU, stakeholders, or both. Table 1 summarizes the possible resources in the ecosystem that LGUs can tap for Digital Democracy activities which are discussed in the paragraphs below.

Table 1: A summary of resources for Digital Democracy initiatives

| Existing resources of the LGU | Budget allocation and procurement | External resources |

|---|---|---|

| Identify key offices and personnel related to the topic of consultation. | Allocate budget for Digital Democracy activities | Collaboration with NGOs, CSOs |

| Identify existing personnel with related expertise (IT Team, Strategic Planning team, legal office, etc.) | Procure related goods and services from external vendors, as supported by the LGU’s Annual Procurement Plan. | Research and extension collaboration with the Academe. |

| Identify existing resources that can be used for data collection and analysis (e.g. existing subscription to survey tools, software, etc.) | Grants and resources from development organizations. |

5.1. Existing Resources of the LGU

LGUs have existing offices, funds, staff, that may be tapped to conduct Digital Democracy activities. The LGU can identify related offices and personnel to coordinate and implement the activities, depending on the consultation topic to be discussed. For example, if the consultation is about a policy on disaster management, the LGU can identify someone from the Planning office, or the Disaster Risk Reduction office to play an active role in the process. LGUs with existing IT offices may also designate IT staff to assist in the process.

If the LGU has existing tools, devices, and expertise related to the activities (e.g. existing programs on internet access in rural areas, existing subscription to data collection and analysis software), these may also be used as key resources on hand.

5.2. Budget Allocation and Procurement

Initiating Digital Democracy initiatives does not necessarily require additional budget. LGUs can make use of existing resources, staff, and software subscription to conduct online consultations.

If the LGU sees the need to procure resources such as additional training, devices, or software, to get the best results of the Digital Democracy process, the LGU may appropriate a budget. Figure 1 below illustrates the Philippine Local Government Unit’s Budget Cycle:

Figure 1: The Philippine LGU Budget Cycle [1]

Suggested additional resources under this topic:

Local Government Code of the Philippines

The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines – Article X

eGovernment Programs of DICT

5.3. External Resources

Partnership with National Government Agencies, the local academe, civil society, and private sector organizations is beneficial to the Digital Democracy process. For example, the Department of ICT has the Tech4Ed project, which deploys digital resources and internet access to rural areas in the Philippines. LGUs may tap programs like these in their Digital Democracy initiatives.

Since Data Analytics can be a highly technical task, the LGU may tap the local academe to assist them in the process. For the dissemination, deployment, and interpretation of analysis results, tapping ICT Councils or People’s Councils may also help.

6. Monitoring and Evaluation

To ensure that objectives of the Digital Democracy activities are met, regular review and assessment both internally and by stakeholders are encouraged. For example, what changed after the consultation? What steps did the government take in response to the suggestions and concerns raised by stakeholders? What policies and programs were created or amended because of the conversation? Did the consultation solve the problem?

6.1. Dimensions to be considered:

6.1.1 Quality of Democracy

What changed after the Digital Democracy activities? Was the problem solved? Were there changes in policies and practices that happened in response to the conversations held?

6.1.2. Public Participation

Who participated in the digital democracy initiatives and from which sectors are they from? Are the participants representative of the entire population concerned? Understanding the number, diversity, and demographic of the participants reflects the quality of public participation in a locality.

6.1.3 Government Responsiveness

Did the government respond to the suggestions of the stakeholders? How did the government receive the insights that were generated from feedback? Citizens are more keen to participate if they can see and feel their LGUs taking action in response to their concerns and suggestions.

6.2. Success Metrics

The Participatory Government Metrics (PGM) can be used to measure the participatory quality of government programs. The PGM is developed by Czarina-Medina Guce under UNDP[2], using 18 Participatory frameworks and indices and is now being piloted to a subset of the Philippine Open Government Partnership commitments. Table 2 provides the indicators discussed in the PGM.

Table 2: Participatory Government Metrics Dimensions to Measure the Participatory Quality of Government Programs

| Dimension 1: Space – The Environment of Participation | |

| Indicators | Key Question |

| Enabling Policy Anchor | To what extent does the program’s enabling policies [1] [LL2] ensure substantive citizen participation? |

| Rationalized Inclusion Criteria | To what extent does the program have clear and rationalized inclusion criteria for participation? |

| Clear Engagement Strategy | To what extent is the program guided by a clear engagement strategy for citizen participation to operationalize the policy mandate? |

| Transparency and Access to Information Protocols | To what extent does the program provide protocols for transparency and public access to information for citizens and interested parties? |

| Organizational Capacity | How sufficient are the program’s manpower and funding to implement citizen participation processes? |

| Functional Mechanism for Communication, Feedback, Petition, and Redress of Grievances | How functional are the program’s mechanisms to communicate, receive feedback, attend the petitions, and to redress grievances of participating citizens? |

| Dimension 2: Engagement – The Process of Participation | |

| Indicators | Key Question |

| Inclusion and Representation | How inclusive and representative is the program of its stakeholders? |

| Autonomy and Fairness | To what extent does the program ensure that engagements with citizens are fair and free from unwanted influence? |

| Transparency of Engagement | To what extent does the program disclose agenda, minutes, and other documentation for the citizens and interested parties? |

| Support to Activities | To what extent does the program support or mobilize resources to support citizen activities? |

| Efficiency of Processes | How efficiently does the program conduct activities/platforms that are practical and accessible for citizens/citizen groups? |

| Dimension 3: Outcomes – The Results of Participation | |

| Indicators | Key Question |

| Influence on Program Decisions | To what extent has citizen participation influenced substantive, high-level decisions in the program (or beyond)? |

| Institutional Changes | To what extent are citizen participation practices changing the program’s policies, ways of doing, and openness in the implementing agency? |

| Program Results | To what extent has citizen participation improved the results (outputs and outcomes) of the program? |

| Citizen Satisfaction on Program | To what extent are the citizens satisfied with their participation in the program? |

Source: Medina-Guce, C. (2020). Participatory Governance Metrics: Tool and Technical Notes. United Nations Development Programme and Department of Interior and Local Government. Accessible here.

6.3. Methods of Evaluation

Evaluation of the results and impact of Digital Democracy initiatives is a critical step in understanding whether the activities are achieving the objectives upon which they were initiated. The results and evaluation of an activity is also a key input to improve its next iteration. The insights and learnings are also valuable inputs in the institutionalization of Digital Democracy activities in a locality.

Below are suggested methods of evaluation by Council of Europe’s Ad Hoc Committee on E-Democracy (CAHDE).

Table 3: Qualitative Methods and Quantitative Methods

| Qualitative Methods | Quantitative Methods |

| Semi-structured Interviews | Registered Users - Usage Statistics |

| Field tests of Digital Democracy Tools | Responses to Questionnaires |

| Online Questionnaire | Messages Posted to Discussion |

| Discourse Analysis | Petitions Raised |

| Analysis of Talk Policies | Names Added to Petitions |

| Internal (government agency) Documentation | |

| Measuring Interactivity | |

| Analyzing Log Files |

6.3.1 Benchmarking

Benchmarking works by comparing the measured participation of an initiative versus other leading initiatives, institutions, and standards. These metrics can be used to monitor a country’s progress over time. How do we know that the Digital Democracy initiatives are working? How much does it influence the digital landscape? How does it compare to other nations?

Below are two metrics that can be used for benchmarking.

6.3.1.1. The e-Participation Index (EPI)

The e-Participation index is a part of the e-Government survey that the United Nations regularly conducts to assess use of online services in governments’ e-consultation, e-information sharing, and e-decision making.[3] It’s currently being used by National Government Agencies such as the Department of Trade and Industry to measure its online service delivery.[4] The EPI is also a qualitative assessment that looks into government websites and e-services, to measure the relevancy of participatory and democratic services. Measuring the EPI is based on three categories:

- E-Information

- E-Consultation

- E-Decision-Making

The EPI aims to assess the quality and usefulness of the information and e-services provided by a government, for the purpose of citizen engagement. The EPI is assessed on a scale of 0 (worst) – 1 (best).

6.3.1.2. The Citizen Participation Measure

The Citizen Participation Measure[5] developed under the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), and the Asian and Pacific Training Center for ICT Development (APCICT). It is used to inspect and evaluate city and municipal websites. For this measure, the citizen participation indicator has six questions that survey the presence and the functions of forums, online decision-making, surveys, and polls.

An assessment of the effectiveness of the Digital Democracy project in Pasig City, Legazpi City, and Intramuros in 2020-2021 was conducted by Makati Business Club and Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. In the process of studying and analyzing the LGUs’ use of digital platforms, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) was adopted, demonstrating the tools' usefulness, ease of use and cost efficiency towards LGUs’ and citizens’ actual digital platforms use.

The study showed that the Digital Democracy project did introduce digital collaboration tools that helped local governments make decisions and improve community participation in democratic processes. In this respect, the project has demonstrated that Pol.is survey tools and other digital platforms are useful, easy to use and cost efficient–provided that (i) all the sectors of society are represented, (ii) there is a strong online consultation infrastructure, and (iii) adequate support is available.

Source: Makati Business Club and Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, MBC-KAS Report on the Digital Democracy Project ‘Strengthening Citizen Participation in Decision-making: A Study on the Adoption of Online Platforms in Select Local Government Units.” November, 2021

6.4. Checklist

The quality of Digital Democracy initiatives must be evaluated by its contributions to the democratic objectives of both the public and governments. According to Council of Europe’s Ad Hoc Committee on E-Democracy (CAHDE), evaluation must cover the following:

- type of engagement (information-consultation-active participation);

- stage in decision-making;

- actors involved;

- technologies used;

- rules of engagement;

- duration and sustainability;

- accessibility;

- resources and promotion;

- evaluation and outcomes;

- critical success factors (to be agreed on before starting the initiative);

- gender aspects and gender mainstreaming.

[2] Medina-Guce, C. (2020). Participatory Governance Metrics: Tool and Technical Notes. United Nations Development Programme and Department of Interior and Local Government. Accessible here.

[3] According to the UN E-Government Knowledge Base the latest EPI of the PH is 0.75. Relative to the other 193 countries monitored by the UN, Philippines is ranked 57 – an improvement from rank 71-75 in 2016. Accessed May 7, 2022.

[4] Department of Trade and Industry. PHL improves scores in United Nations’ e-Participation Index—ARTA pushes GovTech for speedy delivery of government service. Accessed May 7, 2022.

[5] The Citizen Participation Measure developed by Rutgers-SKKU available here.

7. Institutionalization

Different local governments have different resources, capacities and key economic priorities. Some local government units may have better digital infrastructure than others, making it easier for them to institutionalize Digital Democracy in their locality. On the other hand, some local governments need more capacity building on ICT tools and infrastructure for both their staff and stakeholders. This is why it is important to first assess the ICT readiness of an LGU and adopt a gradual and roll-out approach to Digital Democracy institutionalization. Annex 1 also provides the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Council’s recommendations on developing digital government strategies.

Figure 2 below describes how Digital Democracy has three key levels of institutionalization within a Local Government:

Figure 2: Three key levels of Digital Democracy Institutionalization

7.1. Legal Framework

Digital Democracy is supported by the 1987 Philippine constitution, upholding a democratic and republican state. The constitution protects democratic processes under the rule of law. Articles II, X, and XIII emphasize the need to protect the people’s rights to “effective and reasonable participation at all levels of social, political and economic decision-making.”

Some of the existing policies that may be leveraged in support of Digital Democracy are:

- The Local Government Code of 1991 and the Annual General Appropriations Act support and promote citizen participation in governance at the local level.

- House Bill 7950, or the People’s Empowerment Act, creates a People’s Council in every LGU to strengthen citizen participation in various areas of local governance.

7.2. Local Legislation and Regulation

Instruments for the institutionalization of Digital Democracy at the local level are, but are not limited to, the following:

7.2.1. Memorandum Circular

A written report or document prepared and circulated for a specific person, office, or committee, that provides information on a particular matter. An LGU may issue a Memorandum Circular, notifying concerned offices or personnel to actively participate in a Digital Democracy Initiative.

7.2.2. Executive Order

A published directive issued by the Local Chief Executive for implementation or execution of concerned offices. A city mayor, for example, may issue an Executive Order creating a Digital Democracy council in the city, with members from the LGU, Academe, and Civil Society.

7.2.3. Ordinances and Resolutions

The legislations of the LGU. Ordinances and resolutions may be passed by the sangguniang panlalawigan/panglungsod/bayan/barangay. For example, a sanggunian may pass an ordinance that supports and allocates a budget for Digital Democracy initiatives of an LGU.

8. Conclusion

Incorporating Digital Democracy in government decision-making helps policies and projects be more relevant to the needs of the constituents. Actively engaging stakeholders in local government decision-making ensures that government policies and programs are truly addressing the concerns of the community. It allows the government to quickly pivot and/or address emerging issues, preventing them from escalating further.

Embedding Digital Democracy in an LGU’s operations offers many benefits. Having set policies and frameworks within the LGU that support Digital Democracy makes it easier for the LGU staff to conduct their own Digital Democracy activities. For example, should a sudden need to conduct a quick online consultation arises, the LGU already knows who to engage, which tools to use, what questions to ask, and how to draw insights from the people’s feedback.

But because Digital Democracy uses ICT tools as a key component of communication, the ICT readiness of the LGU must first be assessed. For LGUs that are new to Digital Democracy and its use of ICT tools, it is recommended that they start with a Level 1 implementation. Once the LGU gets a better understanding of how their constituents respond to Digital Democracy activities, proceed with a Level 2 implementation, which requires local policies. Finally, the third level of implementation ensures that Digital Democracy is well-integrated into the LGU’s operations and that the LGU can independently initiate Digital Democracy activities whenever they need it. Level 3 implementation suggests the appointment of a Digital Democracy officer as a key point-person to initiate, conduct, and monitor Digital Democracy activities.

Annex 1: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Council released the Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Council released the Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies, to help governments develop strategic approaches on the use of technology to promote innovation and citizen participation. The following are recommendations on developing digital government strategies.

It is recommended that governments develop and implement digital strategies that:

- Ensure openness, transparency, and inclusivity in government processes and operations;

- Promote stakeholder participation in policy-making and public service design and delivery;

- Create a data-driven culture;

- Include a risk management approach to digital security and privacy concerns.

It is recommended that the government do the following in the development of their digital strategies:

- Secure commitment to the strategy from the leaders and key decision-makers;

- Make sure that the use of digital technologies are coherent across policy areas and in all levels of the government;

- Establish governance frameworks that coordinate implementation of the digital strategy internally and across different levels of government; and,

- Strengthen cooperation with other governments.

Finally, it is recommended that governments do the following in the implementation of their digital strategies:

- Have clear use-cases to sustain funding and focused implementation;

- Capacitate institutions in managing and monitoring implementation;

- Procure digital technologies based on existing assets, resources, and objectives;

- Ensure that the legal and regulatory frameworks allow digital opportunities to be seized.

Acknowledgments

- Frei Sangil

- Data Scientist, Layertech Software Labs

- Engr. Lenidy Mañago

- Research Specialist, Mañago Engineering Consultancy

- Lany Laguna-Maceda, DIT

- Associate Professor, Bicol University College of Science

- Administrator (Atty.) Guiller Asido

- Administrator, Intramuros Administration

- Rodrigo S. Magat

- Consultant and Board Secretary

- Intramuros Administration

- Fr. Jose Victor E. Lobrigo

- President and CEO, SEDP (Simbag sa Pagasenso, Inc.)

- Carlos “Chito” Ante

- City Administrator, Legazpi City

- Rosemarie Quinto-Rey

- President, Albay Chamber of Commerce and Industry

- Honelet Soreda-Bertis

- Legal Officer/Secretary General, Albay Chamber of Commerce and Industry

- Michael Lagcao

- Office of the Vice Mayor, Iligan City

- Karen May Crisostomo

- Pasig Transport Office

- Ms. Czarina Medina-Guce

- Governance Specialist, UNDP, and Lecturer at Ateneo de Manila University

- Luz G. Galda

- OIC – Division Chief, Business Development Division, DTI – Lanao del Norte

- Ma. Welissa V. Domingo

- Head, SME Development Unit, DTI – Lanao del Norte

Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International

The contents of this material can be used in any way permitted by the copyright and related legislation that applies to the intended use. No permission is required from the rights-holders for non-commercial use. However, attribution is required for the modification and dissemination of this handbook and its contents.

Please credit and/or link to Makati Business Club.

For more information, concerns, and queries, please contact: MBC Secretariat at makatibusinessclub@mbc.com.ph

The Digital Democracy Project