Digital Democracy Handbook

Digital Democracy in the Middle of the Pandemic

Lessons from 5 Pilot Projects

Book 3

A Review of Concepts

Table of Contents

1. Executive Summary

Digital Democracy is using information and communication technology (ICT) in all kinds of media to enhance democracy or citizen participation in government decision-making. The Digital Democracy process is multi-sectoral, involving stakeholders from the Local Government Unit (LGU), Civil Society Organizations (CSO), business, academia, media, and individuals. The strength of the process is participation of diverse stakeholders, providing a wide range of ideas and suggestions to co-create solutions, programs, and policies.

The use of digital tools and platforms can help uphold good governance.

e-Governance or electronic governance is the use of digital means by public administration to exercise its functions and deliver public services.[1] Digital Democracy is a part of e-Governance, and a driver for good governance.

According to the definition of the Office of Ombudsman and UNDP Philippines[2], good governance ensures that political, social, and economic priorities are based on broad consensus in society and that the voices of the poorest and the most vulnerable are heard in decision-making over the allocation of development resources.

There are eight characteristics of good governance (see Figure 1 in Section 4 of this handbook) according to the United Nations Development Program (UNDP): Participatory, Consensus-Oriented, Accountable, Transparent, Responsive, Effective and Efficient, Equitable and Inclusive, and follows the rule of law.

2. Scope and Delimitation

This material serves as a general guide designed for all actors at all levels of the implementation of a Digital Democracy initiative and could provide an overview of the diverse opportunities to start Digital Democracy activities in their respective offices.

This material does not attempt to address all possible procedures or methods of Digital Democracy or imply that it is limited to the contents of this material. Readers are urged to view this handbook as an initial guide; to supplement their knowledge on the possible uses of ICT tools, procedures, and methods to enhance democratic processes, and inform decision-making and policy-making at the local government level. Finally, this material is not meant to replace domestic policies and procedures.

3. What is Digital Democracy?

Digital Democracy is the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in all kinds of media for purposes of enhancing political democracy or the participation of citizens in democratic communication. It does not aim to replace traditional, face-to-face consultations. Instead, it complements and reinforces existing democratic practices by introducing ICT tools and new ICT-related innovations.

3.1. Who is Involved?

The Digital Democracy process is a multi-sectoral endeavor, from the Local Government Unit (LGU), Civil Society Organizations (CSO), Business Organizations, Academia, Media, up to the individual constituents. The strength of the Digital Democracy process lies with the participation of diverse stakeholders, providing a wide range of ideas and suggestions to co-create solutions, programs, and policies.

3.2. Benefits and Applications of E-Governance

Leveraging digital tools and platforms offer numerous benefits for both LGUs and stakeholders. Books 1 and 2 of this series discusses the benefits and results of conducting Digital Democracy processes in Pasig, Legazpi and Iligan cities as well as in Intramuros.

Based on LGU assessment of MBC-led Digital Democracy processes, some of the key benefits of adopting Digital Democracy initiatives are the following:

3.2.1. Strengthens cooperation and communication between public authorities and communities:

The use of digital tools can improve communication between local authorities and their constituents, allowing LGUs to identify key concerns. This gives the LGU more time and insight to respond and address the issues raised via policy changes or new initiatives. Similarly, constituents are encouraged to participate, give feedback, and share their expertise, helping LGUs craft more effective and inclusive programs and policies.

3.2.2. Informs government decision-making with data.

Having documented citizen feedback and machine-readable datasets allows the government to leverage Data Science to inform decision-making, predict possible bottlenecks and pitfalls, and proactively prepare for future challenges.

3.2.3. Enhances resilience in the face of emergencies:

Use of digital tools and platforms proved to be a strategic asset during the Covid-19 pandemic. A robust digital infrastructure helps ensure continuity in the activities of key institutions and the provision of essential services to the public, especially in the face of an emergency.

3.2.4. Makes the local government more attractive to business and investment:

Ease of doing business can be a strategic advantage of LGUs. Use of digital tools helps streamline transactions, resulting in faster and improved service delivery to constituents.

Note, however, that since the primary actors of Digital Democracy initiatives are government offices, it is important that the government office (or the local leadership, for Local Government Units) are willing to ask for feedback and their constituents are willing to give it.

4. Good Governance

The use of digital tools and platforms can help uphold good governance in localities. According to the definition of the Office of Ombudsman and UNDP Philippines[3], good governance ensures that political, social, and economic priorities are based on broad consensus in society and that the voices of the poorest and the most vulnerable are heard in decision-making over the allocation of development resources.

4.1. Characteristics of Good Governance

There are eight characteristics of good governance (see Figure 2) according to the United Nations Development Program (UNDP):

Figure 1: The eight characteristics of good governance according to UNDP, accessible here.

Participatory

All constituents should have a voice in government decisions and policy-making, either directly or through legitimate institutions or representatives. Citizens should be informed, and capacitated to participate, protected by freedom of association and speech.

Consensus Oriented

Differing interests are mediated to reach a broad consensus among different sectors in the community.

Accountable

The key decision-makers in the community, whether it is from the government, the private sector, or civil society organizations, are all held accountable to the public, especially to those who will be most impacted by their actions.

Transparent

Complete, up-to-date, and relevant information about government decisions, processes, policies, and their implementation are freely accessible, especially to stakeholders who are most affected.

Responsive

Institutions and processes serve all stakeholders within a reasonable amount of time.

Effective and Efficient

Processes and institutions are producing results that are sustainable and meet the needs of their stakeholders while making the best use of available resources.

Equitable and Inclusive

All members of the community, regardless of age, race, gender, and social status have equal access to services and opportunities in society. The most vulnerable are protected and ensured to have the opportunity to improve their well-being.

Follows the Rule of Law

Fair and legal frameworks are enforced impartially, with full protection of human rights, particularly those of the vulnerable and minorities.

Digital Democracy helps enable Good Governance by leveraging digital tools to encourage citizen participation in government decision-making, helping make government transactions and services more transparent and accessible to their constituents. For example, the use of online survey forms and online video conferencing software helped collect feedback from constituents regarding a proposed policy, amid the limitations brought by Covid-19.

5. e-Governance

Digital Democracy leverages ICT tools to promote citizen participation. Digital Democracy initiatives can be considered a part of a government entity’s e-Governance policy.

5.1. What is e-Governance?

e-Governance or electronic governance is the use of digital means by the public administration (at all levels) to exercise its functions and deliver public services[4]. Examples of e-Governance initiatives are, but not limited to, the following:

- Using Information Systems to streamline local government business processes, resulting in improved records management and service delivery.

- Use of multiple digital platforms (internet, mobile messaging, off-line) to receive and respond to emergencies.

- Data collection and analysis of citizen feedback to inform local government decision-making and policy-making.

- Use of mobile applications, online portals to promote the LGU for business and tourism.

- Use of e-Payment tools and platforms to make tax collection and payments faster and more convenient to constituents.

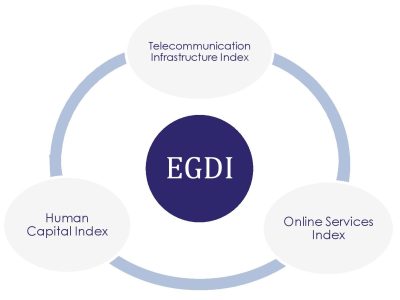

5.2. e-Government Development Index (EGDI)

The EGDI is a composite indicator by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) that is used to measure the readiness and capacity of national institutions to use ICTs to deliver public services and assesses the e-Government development status.

LGUs may use (or take inspiration from) the EGDI’s indices to assess their own readiness to explore and institutionalize the use of digital tools in their decision-making or operations. It can be used as a metric to monitor the LGU’s improvement in terms of digital capacity over time.

The EGDI is based on a comprehensive survey of the online presence of all United Nations Member States’ governments. The assessment rates the e-Government performance (discussed below in section 4.21-4.2.3) of countries relative to one another as opposed to being an absolute measurement. The results are tabulated and combined with a set of indicators embodying a country’s capacity to participate in the information society, without which e-Government development efforts are of limited immediate use. Table 1 shows the EGDI range values and its corresponding indicator.

Table 1: EGDI range values and corresponding indicator

| Very High | 0.75-1.00 |

| High | 0.50-0.74 |

| Middle | 0.25-0.49 |

| Low | 0.00-0.24 |

Source: Congressional Policy and Budget Research Department House of Representatives (CPBRD).

Facts in Figures: E-Government Development and E-Participation Indices, 2020. 2021. Accessible here.

Table 2 shows the ASEAN member-countries’ constant increases in their EGDIs from 2014 to 2020, except for Cambodia, Laos, and Singapore which recorded EGDI fluctuations. The Philippines’ EGDI scores lie in the mid-range at 0.48 (2014), 0.58 (2016), 0.65 (2018) and 0.69 (2020)[5].

Table 2: EGDI, ASEAN (2014-2020)

| Country | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 | 2020 |

| Singapore | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.92 |

| Malaysia | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.72 | 0.79 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.69 | 0.74 |

| Philippines | 0.48 | 0.58 | 0.65 | 0.69 |

| Thailand | 0.46 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.76 |

| Vietnam | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.67 |

| Indonesia | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.66 |

| Cambodia | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.51 |

| Lao People’s Democratic Republic | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.33 |

| Timor-Leste | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.46 |

| Myanmar | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.43 |

Source: Congressional Policy and Budget Research Department House of Representatives (CPBRD).

Facts in Figures: E-Government Development and E-Participation Indices, 2020. 2021. Accessible here.

The EGDI consists of three indices that are equally weighted:

5.2.1. Telecommunication Infrastructure Index

The TII measures the existing infrastructure that is required for citizens to participate in e-Government. It is composed of four indicators:

- estimated internet users

- number of mobile subscribers;

- active mobile-broadband subscription; and,

- number of fixed broadband subscriptions with high-speed access to public internet.

5.2.2. Human Capital Index (HCI)

The HCI is used to measure citizens’ ability to use e-Government services. It consists of four components:

- Audit literacy rate;

- Combined primary, secondary, and tertiary gross enrollment ratio;

- Expected years of schooling; and,

- Average years of schooling.

5.2.3. Online Service Index (OSI)

The OSI measures a government’s capability and willingness to provide services and communicate with its citizens electronically. This index evaluates the provision of online services by Governments and assesses the availability of online transactional services on government portals.

[4] Definition of e-Governance from the E-Democracy Handbook published by the European Committee on Democracy and Governance.

[5] Congressional Policy and Budget Research Department House of Representatives (CPBRD). Facts in Figures: E-Government Development and E-Participation Indices, 2020. 2021. Accessible here.

6. An Overview of Tools used in Digital Democracy

6.1. Online Consultation

An Online Consultation refers to an exchange between the government and citizens using the Internet (such as via Zoom or other teleconferencing applications). This method collects opinions of designated persons or the public at large on a specific policy issue to inform the succeeding actions and decisions of key decision-makers[6].

An online consultation is a key tool in the Digital Democracy process. Book 2 presents various tools LGUs can use to conduct online consultations.

Online consultations are especially useful in circumstances where face to face interaction is challenging. This is particularly evident in the Covid-19 pandemic, wherein digital platforms were the only available means to conduct meetings amid lockdowns. Online consultations also allow recording of conversations, useful for record-keeping. Online consultations have the potential to increase the reach of governments to their constituents.

6.2. Online Feedback Collection / Survey

Online surveys allow LGUs to collect citizen sentiments without having to meet the respondents face to face. Book 2 provides various tools which LGUs can use to initiate online feedback collection.

Many online survey platforms like Pol.Is and Google Forms offer immediate aggregation of results, which makes tabulation and visualization faster and easier. Furthermore, many online survey tools and platforms offer anonymity to respondents, encouraging stakeholders to share honest thoughts and feelings about the topic or issue. Various digital tools and online platforms allow hosts to create and deploy survey forms. The use of these tools has the potential to reach a wider range of constituents in the locality.

6.2.1. Web Portal

A web portal refers to a website specially designed to be used as an information source. Unlike a typical public website, web portals restrict content access only for defined users. Web portals also offer features that allow users to interact and make controlled changes to its contents.[7]

Figure 2: The Philippines’ eFOI portal is an example of a web portal wherein users can actively interact with the site, submit requests and contribute to the database.

Government web portals support the citizens in dealing with public authorities by electronic means such as web-based platforms for communicating and transacting with public authorities.

Having a web portal can be beneficial in implementing Digital Democracy. Updates, actions taken, documentation, and other relevant information may be published in a single portal which stakeholders may refer to, and respond to, at any time. This can either be a part of the government’s official website, a standalone portal, or an existing web portal service specially designed for citizen feedback monitoring and analytics.

6.2.2. Webcasts

Webcasts refer to the live streaming of legislative / executive / judiciary meetings over the Internet by public authorities, providing citizens and other interested stakeholders with information and increasing transparency.

Webcasts are great tools in engaging stakeholders in the Digital Democracy process. It helps keep constituents updated on feedback collection, analysis, and how the government responded to their feedback.

Since the Philippines is one of the biggest social media users in the world, leveraging popular social media platforms to perform webcasts (such as Facebook Live) may prove beneficial to maximizing the reach of the Digital Democracy initiative. Citizen assemblies and survey reports for example, are live-streamed using Facebook to reach a wider audience. Furthermore, keeping constituents updated about the efforts of the government to reach out and work with them tends to increase favorability and cooperation.

7. Global Best Practices

The following are policies and practices related to e-Governance that have become topical in many countries and have been proven to help in ensuring continuity of government services, especially during the Covid-19 emergency. LGUs may use these policies, or take inspiration from them, in running their own Digital Democracy initiatives.

7.1. Incentivizing Participation

Given the overflowing information and content on the internet, sometimes, it can be really challenging to get the attention of stakeholders and get them to participate in Digital Democracy activities such as filling out surveys, or attending assemblies online.

Stakeholders can be encouraged to participate by giving them incentives[8]. Incentives do not necessarily mean monetary or material incentives. Introducing the audience to a free platform which may be useful to their day-to-day lives is already a form of incentive. Incentives may also take the form of faster resolution to citizen concerns, faster government transactions, and improved responsiveness to feedback and queries. All of these are incentives.

Giving incentives helps increase citizen participation during dialogues, surveys, resulting in better representation of the constituency, and a richer pool of feedback and insights for government decision-making.

It is useful to reflect on the incentives that the participants will have if they are constantly joining Digital Democracy activities, or answering surveys. Some examples of incentives are:

Direct Material Incentives

These are straightforward incentives for participation in Digital Democracy activities. For example, attendees may receive cellular load to access the online assemblies, or are paid compensation for wages lost when participating in citizen assemblies.[9] Gift certificates, cash cards, and discount vouchers may also be given as direct incentives when encouraging participants to answer the survey.

Choose tools that are simple, easy to use, and make life and work easier for the target participants.

Providing tools that make users’ lives and work easier is already an incentive, by itself. If users find digital tools and platforms easy to use and accessible, they will be more encouraged to participate in Digital Democracy activities

Close the feedback loop. Give updates on how the government acted in response to citizen feedback.

Closing the feedback loop, in itself, is a key incentive. Citizens would not be enthusiastic to give their feedback if they can see that it is not valued nor considered by the government. For example, it was observed by Layertech labs in Legazpi City that simple updates in social media, can help encourage citizens to keep on participating in Digital Democracy activities.

Certificates and tokens of appreciation

If available, small tokens (such as gift coupons, stationery, giveaways, etc.) may be given to participants to show appreciation for sharing their time and insights with the government. Another common token to distribute would be to provide a certificate of attendance or appreciation to participants.

Social media mentions and acknowledgment

In the age of social media and digital platforms, posting documentation and publicly acknowledging the contribution and participation of the organizations that participated may hold value.

7.2. Building Stakeholders ICT Skills

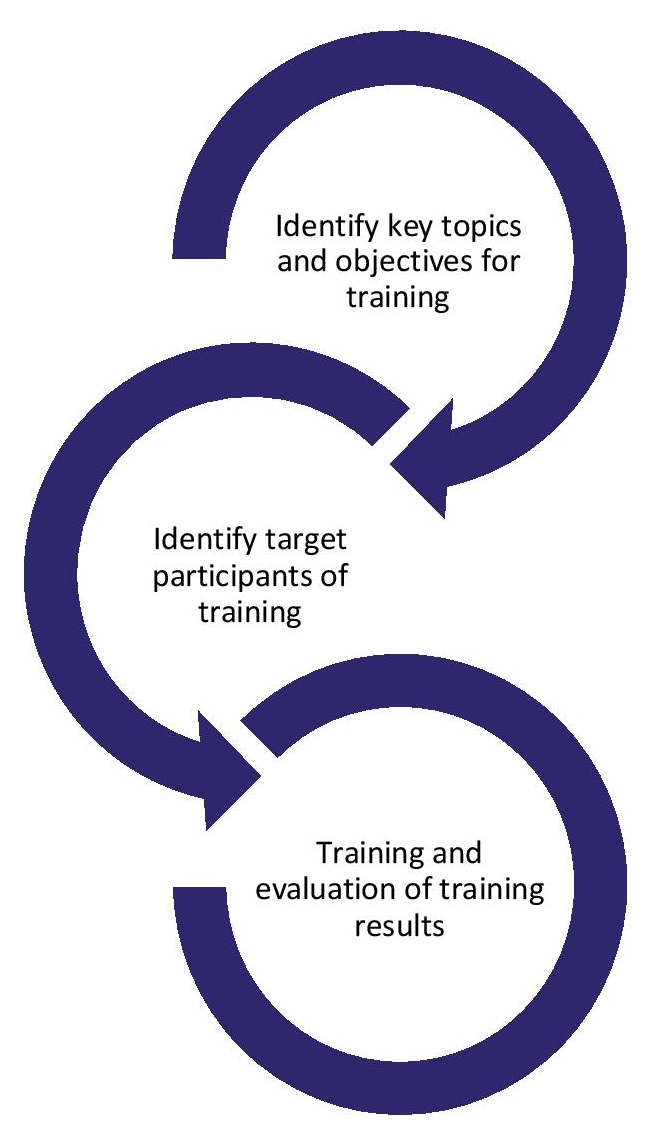

Digital tools and platforms play a key role in Digital Democracy. It is critical that participants of the process are well-equipped with the knowledge and skills in relevant ICT-based topics. If stakeholders are not knowledgeable about digital tools, then how can they participate in the process? Building stakeholders ICT skills through training initiatives can be a great supplement in institutionalizing Digital Democracy in your LGU. This training can also be expanded to other members of civil institutions.

Developing media competence, training, and creating expert groups for Digital Democracy within the public authority are usually the main objectives of the initiative. As a result, the trained and informed civil servants can enable further government Digital Democracy initiatives.

Building ICT capacity can be initiated either by governments or the private sector, depending on the topic, training objectives, or availability of resources and expertise. Figure 3 presents a guide on how capacity building sessions can be planned.

Identify key ICT topics and objectives for training

- What are we hoping to achieve in this training?

- What are the learning performance indicators?

- What are the relevant ICT topics to be discussed?

Identify target participants of training

- Who should attend the training?

- What do we hope for the participants to do after the training?

Training and evaluation of results

- How will we deliver the training?

- What tools, platforms to use and are these accessible to target participants?

- Evaluation options

- Options can be tests or quizzes, sharing of insights, or written reports of progress.

Figure 3: Flowchart and guide questions for planning an ICT capacity building session

7.3. Other Best Practices

Table 3 presents other policies and practices that are commonly used and associated with Digital Democracy. These are referenced from the Council of Europe ‘Ad hoc Committee on electronic democracy’ (CAHDE) and may be replicated in similar applicable contexts.

Table 3: Policies commonly associated with Digital Democracy initiatives

| Policy | Description |

|---|---|

| Digital Inclusion | These are activities by public authorities and NGOs to promote inclusion in Digital Democracy, especially of the unconnected, the elderly, minorities, other marginalized socio-economic groups, and citizens with special needs. |

| Overcoming e-Obstacles | These are activities to eliminate barriers of access, and use of Digital Democracy, especially the issues of digital divide and digital illiteracy. Examples would be digital literacy training and distribution of devices and portable internet access points. |

| Government Interactivity With Citizens: Government to Citizens (G2C) with Citizen to Citizen (C2C) | These are initiatives by public authorities to support grassroots-based digital initiatives. Public authorities may either financially support digital initiatives or integrate them into their standard processes. For example, a government office may officially adopt a mobile app developed by a local start-up company, because it was proven to improve communication with constituents. |

Source: Council of Europe ‘Ad hoc Committee on electronic democracy’ (CAHDE). Electronic democracy (“e-democracy”) Recommendation CM/Rec(2009) and explanatory memorandum. February 2019. Accessible here.

[8] From Game Theory for Data Science: Eliciting Truthful Information by Boi Faltings and Goran Radanovic (2017) published by Morgan and Claypool

[9] From discussion with Dr. Nicole Curato, Professor of Political Sociology at the Centre for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance at the University of Canberra on the “Labor of Democracy”.

8. Conclusion

Experiences of using digital tools, its key lessons, and best practices are available in published documents by global institutions such as UNDP, World Bank, and CAHDE. Although LGUs in the Philippines have their own unique contexts, needs, resources, and priorities, learning from these best practices and proposed frameworks will help local decision-makers better initiate and implement Digital Democracy in their constituency.

Acknowledgments

- Frei Sangil

- Data Scientist, Layertech Software Labs

- Engr. Lenidy Mañago

- Research Specialist, Mañago Engineering Consultancy

- Lany Laguna-Maceda, DIT

- Associate Professor, Bicol University College of Science

- Administrator (Atty.) Guiller Asido

- Administrator, Intramuros Administration

- Rodrigo S. Magat

- Consultant and Board Secretary

- Intramuros Administration

- Fr. Jose Victor E. Lobrigo

- President and CEO, SEDP (Simbag sa Pagasenso, Inc.)

- Carlos “Chito” Ante

- City Administrator, Legazpi City

- Rosemarie Quinto-Rey

- President, Albay Chamber of Commerce and Industry

- Honelet Soreda-Bertis

- Legal Officer/Secretary General, Albay Chamber of Commerce and Industry

- Michael Lagcao

- Office of the Vice Mayor, Iligan City

- Karen May Crisostomo

- Pasig Transport Office

- Ms. Czarina Medina-Guce

- Governance Specialist, UNDP, and Lecturer at Ateneo de Manila University

- Luz G. Galda

- OIC – Division Chief, Business Development Division, DTI – Lanao del Norte

- Ma. Welissa V. Domingo

- Head, SME Development Unit, DTI – Lanao del Norte

Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International

The contents of this material can be used in any way permitted by the copyright and related legislation that applies to the intended use. No permission is required from the rights-holders for non-commercial use. However, attribution is required for the modification and dissemination of this handbook and its contents.

Please credit and/or link to Makati Business Club.

For more information, concerns, and queries, please contact: MBC Secretariat at makatibusinessclub@mbc.com.ph

The Digital Democracy Project