Digital Democracy Handbook

Digital Democracy in the Middle of the Pandemic

Lessons from 5 Pilot Projects

Book 2

Insights on the Digital Democracy Process

Table of Contents

1. Executive Summary

The use and integration of digital tools in local government policy and decision-making requires preparation, gradual roll-out, and regular monitoring to ensure effectiveness and inclusivity.

Some key lessons to keep in mind are:

- Involve your stakeholders throughout the process—from hosting an initial meeting, identifying key information requirements, to deciding on appropriate tools and platforms to use for the consultation.

- Use both online and offline platforms to reach as many stakeholders as possible: Social Media, Civil Society, and Punong Barangays.

- Use simple, straightforward, and concrete language when communicating with stakeholders. Not everyone wants to learn jargon!

- Visualize data collected. Use applicable graphs, infographics, and present results in a closing assembly to validate the insights collected, or drive meaningful conversations

- Finally, close the feedback loop. People will want to participate in consultations and cooperate with new policies if they see that their feedback is being used to improve the city. Inform citizens of actions made in response to the feedback.

The Digital Democracy handbooks aim to provide government officials with the tools to initiate a Digital Democracy project in their own cities or agencies. This enables the government to make better decisions informed by citizen input while at the same time, strengthening civic engagement. This second handbook will help LGUs plan their own Digital Democracy consultation, supported with examples from MBC’s 2020 and 2021 Digital Democracy projects in Pasig, Legazpi, and Iligan cities as well as in Intramuros.

2. Scope and Delimitation

This material serves as a general guide designed for all actors at all levels of the implementation of a Digital Democracy initiative and could provide an overview of the diverse opportunities to start Digital Democracy activities in their respective offices.

This material does not attempt to address all possible procedures or methods of Digital Democracy or imply that it is limited to the contents of this material. Readers are urged to view this handbook as an initial guide; to supplement their knowledge on the possible uses of ICT tools, procedures, and methods to enhance democratic processes, and inform decision-making and policy-making at the local government level. Finally, this material is not meant to replace domestic policies and procedures.

3. Introduction

Makati Business Club (MBC) conducted 5 Digital Democracy initiatives from 2020-2021 in Pasig, Legazpi, Iligan, and in Intramuros. In these areas, MBC introduced digital tools to improve government consultations online.

The Digital Democracy process can be summarized in the following steps:

- Planning

- Formulation of Survey Questions

- Holding an Opening Citizen Assembly

- Collection and Analysis of Feedback Data

- Conducting a Closing Citizen Assembly

- Closing the Feedback Loop

This document presents in detail the Digital Democracy process, and the lessons learned from MBC and Layertech’s experiences in conducting the Digital Democracy project and its pilot cases in 2020-2021. The goal of this handbook is to serve as an initial guide for government offices and their stakeholders on running their own Digital Democracy initiatives.

4. The Digital Democracy Process

Step 1: Planning

Choosing a Topic

In the planning stage, you and your team should choose an issue as the focus of the Digital Democracy process. This issue answers the question “On what issues do we need the community’s feedback?” — the issue can be a new policy that the LGU is considering or controversial issues where the LGU wants guidance.

The narrower the topic, the more direct the feedback from communities will be. For example, Pasig City chose a broad topic – “Low-Speed Streets” — because they wanted to get broad input from community members on lower speed limits as well as gather suggestions on which streets might be suitable for the new policy.

The Pasig City Transport office was considering lowering speed limits within the city center to lessen fatalities and serious injury in car accidents. The LGU knew that this policy would be controversial among Pasig City residents – lower speed limits might be seen as worsening traffic in an already congested city center. Pasig City officials chose the topic “Low-Speed Streets” for their Digital Democracy process to ask Pasig city residents, students, and workers what they think about the policy.

On the other hand, Intramuros Administration chose a narrow topic of “Pedestrianization of Heneral Luna St.” because they already had a clear scope for their policy, and wanted to avoid misconceptions that streets vital to motor vehicles would be closed off. Intramuros Administration wanted to preserve the San Agustin Church, and Intramuros’ famous cobblestones so they were thinking about blocking motorized vehicles from Heneral Luna St. itself and selected streets around it to lessen vibrations that damage the stone facade of the church and the cobblestones on the surrounding streets. Intramuros decided on the topic “Pedestrianization of Heneral Luna St” for their Digital Democracy process. The topic is both clear and specific — by naming the street that the Intramuros Administration is considering blocking off, they avoid off-topic debates about other streets within Intramuros.

Project Planning

After defining a set issue or topic for the Digital Democracy process, we recommend identifying and meeting with key stakeholders, such as other offices or officials within the Local Government Unit, or within the provincial or national government.

This meeting will identify the objectives, target output, and strategy of the project including decisions on the following:

- Information requirements for the survey where the team identifies what it is the LGU wants to learn from their citizens.

- How to communicate details about the topic to citizens and communities

- Which platforms or tools to use to disseminate the survey and gather feedback

- What format to use for citizen assemblies (in person, hybrid, fully online)

- Which partners/experts to tap to analyze and interpret the data

- What timelines and deadlines for the project. See Figure 1 for a recommended timeline.

Figure 1: Recommended timeline to consider when planning for a Digital Democracy process.

Check in with the leader of your LGU or government agency and ensure that they support the Digital Democracy process. The Mayors of Pasig and Legazpi City, the Vice Mayor of Iligan City, and the Administrator of Intramuros supported the process by assigning LGU staff to assist the organizers and participating in the citizen assemblies. Their participation ensured that the topic and feedback were useful for the LGU and lead to action after the process is finished. All four leaders can make use of the feedback from the Digital Democracy process to shape policymaking.

Section 5 of this article provides tips on creating a Digital Democracy action plan for implementation.

Identifying Actors and Stakeholders

Figure 2 presents a Digital Democracy stakeholder map and its key actors. Actors under the government (in red circle) are usually the key initiators of Digital Democracy initiatives while the non-government actors (in yellow circle) provide valuable resources such as feedback, ground insights, technical expertise, and information dissemination capabilities. It should be noted that all stakeholders, especially CSOs and NGOs can also initiate the Digital Democracy process, in collaboration with the LGU officers. Discussion on the Digital Democracy officer can be found in Book 4 of this series.

One key aspect for the success of any Digital Democracy initiative is to get the various stakeholders in the ecosystem involved in the process. According to Layertech, a data science organization and Digital Democracy partner, having a well-represented citizen assembly allows the government to collect rich and encompassing insights.[1] This leads to more accurate, relevant, and effective insights for government decision-making.

Figure 2: Digital Democracy stakeholder map

[1] This is based on a statistical sampling technique called ‘stratified sampling.’ Because it’s impossible to collect feedback data from every single person in Pasig, the Digital Democracy team will only collect ‘samples’ and approximate insights from it. However, in order for the sample collected to accurately represent the thoughts and insights of the entire population, the team must collect ‘samples’ from key sectors in the community, so that each sector is properly represented. The idea is from statistics, but it translates to the quality of insights collected in practice. For more information, see this link.

Step 2: Formulating Survey Questions

Based on our experience conducting Digital Democracy initiatives, how questions are phrased is crucial for the survey process – phrasing may affect how respondents answer the survey and how accurately the survey results reflect their opinions, experiences, and behaviors.

Below are some important things to consider when formulating questions for the survey.

- Ask questions that are clear and specific. Use simple and concrete language to be easily understood by respondents.

- Don’t use jargon or unfamiliar abbreviations. Consider using familiar terms to the community. An example is from the Digital Democracy pilot run on Iligan LGU’s “Supporting Small Family Businesses” in 2021: Nangihanglan ko ug tabang para makacomply sa balaod sa pag negosyo/freelancing. (I need support in compliance with the law about doing business/freelancing.)

- Avoid making your questions redundant (e.g. don’t write: ‘Are you in high school?’ and ‘Are you NOT in high school?’) Keep the questionnaire as SHORT as possible.

- Consider whether certain words may be viewed as biased or potentially offensive to some respondents. For example, do not use racial slurs against minority groups (e.g. the Chinese-Filipino community, ethnic groups). Another example would be asking: “Are you only an elementary school graduate?” Better would be to ask “What is your highest educational attainment?”

- Be mindful of how you use the information collected. Make sure that the questions do not violate the Data Privacy Act of 2012. In the event that personal information IS collected, exercise reasonable caution and proper handling and carefully delete the personal information after a prescribed period. More information about the Data Privacy Act of 2012 can be found in Annex 1.

- Consider testing new survey questions ahead of time (e.g., through focus groups) since this may help identify gaps and redundant or unclear questions. If the LGU has a tighter timeline, the LGU may ask a representative from a civil society organization to comment on the survey before distributing it to the public. This way, the LGU can identify if all the questions are relevant to the policy topic.

Section 6 presents various tools that LGUs can use to create questionnaires and collect feedback data.

During the citizen assembly in Legazpi City, some respondents found the questionnaire too long and started answering the survey haphazardly (data analysis by Layertech Labs was able to capture this dimension of the feedback received, and accounted for this during their review). Some respondents even expressed their irritation at the length of the questionnaire in the comments section.

To ensure meaningful participation, it is recommended that a feedback collection form should consist of no more than 10-20 statements or questions. Although the ideal length would still depend on the key information requirements of the LGU, it is important to remember to keep the questionnaire as short and simple as possible by only collecting information that is useful and relevant to the topic.

Step 3: Opening Citizen Assembly

A citizens’ assembly is an event where members of the community take part in government decision-making. An assembly would have a randomly selected group of residents with different genders, ages, or income levels. The role of a citizens’ assembly is to analyze a given problem, deliberate on different solutions to this problem, and then make an informed decision.

As part of the Digital Democracy process, it is recommended that the LGU hosts an opening citizen assembly where LGU officials present their objectives for soliciting feedback, and how this feedback would be used to benefit their plans and projects for this issue.

Having the heads of the LGU and government agencies participating in the citizen assemblies in 2020 and 2021 demonstrated to civil society groups and communities that the results of the activity would be heard by the decision-makers, and that action would be taken based on their feedback. This is important to encourage participants to respond to the online survey and participate in the assemblies.

Hybrid events should be considered when possible. On one hand, physical events create a sense of community and are more accessible for less tech-savvy members of the community. The dynamics of physical gatherings may make community members more amenable to compromise and finding solutions. On the other hand, online platforms are important in soliciting feedback from constituents who are not present in the physical meeting room due to various constraints and circumstances. Furthermore, video records uploaded online allow constituents who were not able to attend the live meeting to still listen to the presentations and discussions of the citizen assembly. The combination of physical and online participation may make citizen assemblies more inclusive.

Book 4 of this series presents a list of video conferencing tools that LGUs can use to host citizen assemblies.

Who should be invited to the Citizen Assembly?

Invitees to most citizens’ assemblies are recruited to reflect the wider public in terms of gender, age, location of residence, ethnicity, and other criteria. LGUs could also invite civil society organizations and sectoral representatives from the community, especially those who are most affected by the topic to be discussed. Some key points to consider when identifying invitees:

- The issue: depending on the topic, you might want to recruit people according to their background. Based on MBC’s experience conducting Digital Democracy processes, having diverse perspectives represented in the assembly tends to improve the quality of deliberation since it brings new ideas and nuances to the discussion. The Pasig City citizen assembly on Open Streets included representatives of religious groups who emphasized the need for car access on worship days to account for worshippers living outside Pasig city.

Having experts participate in the citizen assemblies provides context to the participants on the purpose of the listening. For example, during the Pasig citizen assembly in 2021, Robert Anthony Siy, Head of Pasig Transport, participated in the citizen assemblies and was able to debunk myths that lowering the speed limit results in traffic.

- The context: the local context and nature of the topic may also influence the criteria and quotas you choose to recruit by. In some cases, it might be right to “oversample” certain groups. Oversampling means that more of one group is invited to the assembly than on other groups. This is relevant for Digital Democracy processes that have a disproportionate impact on one group than other groups. In a citizen assembly talking about suggestions for government assistance to MSMEs, more small business owners should be invited.

The Citizen Assembly in Iligan City 2021 invited a diverse group of stakeholders including local bank representatives, students, freelancers, and small business owners. By inviting a variety of participants to the assembly, the government ensured that all stakeholders are (1) alerted to the feedback collection ongoing, (2) provided the opportunity to give inputs into the feedback collection process, and (3) discuss among themselves ideas and recommendations to address the issue on hand. In this way, the government gained meaningful participation and information about how to address the issue.

On the other hand, during the citizen assembly in Legazpi, the LGU was most interested in hearing from small business owners on what support they needed from the government to better recover from the impact of COVID-19 on their businesses. During the citizen assemblies, a larger number of small business owners were invited to participate (i.e. they were oversampled) to (1) increase the reach of the questionnaire to the targeted group of people, (2) to provide the government with recommendations from the affected group of people and (3) establish a connection between the government and the affected people.

Choosing attendees to an online citizen assembly

Once the team determines[2] the key sectors or demographics that are relevant to the policy/subject (e.g. women, PWDs, bikers, MSMEs, etc.), the LGUs may want to do an additional step: choose representatives among these key sectors who will discuss their survey answers in-detail. Table 1 shows proposed information dissemination strategies for target participants. Hybrid citizen assemblies may use any of the strategies below.

Table 1: Proposed information dissemination strategies

| OFF-LINE | ON-LINE |

|---|---|

| Send invitations to other departments or teams in the LGU, civil society organizations, academic organizations, schools, universities, and business organizations within the locality. | Send invitations via email to identified stakeholder groups. |

| Tap the local media to announce the citizen assembly (only if the physical meeting place accepts public walk-ins) | Tap the local media to announce the online assembly and on which platforms it may be accessed |

| Course through the punong barangays to invite their constituents, especially priority sectors | Post invitations and announcements in social media pages and relevant groups. |

| Post an invitation on the public announcement board/s (only if a physical meeting place accepts public walk-ins). | (optional) leverage targeted advertising to increase the reach of the post. |

[2] ‘Stratified sampling’ is the statistical term for choosing respondents based on identified key ‘sectors’ or subgroups within an entire population. It means that every key sector needs to be equally represented.

Step 4: Dissemination and Analysis of the Survey

The survey can be disseminated online and offline. The suggested response time is 3-4 weeks, to allow citizens’ assembly attendees and others ample time to reflect on and answer the questions.

The ideal survey conditions may not always happen, but taking note of collection methods, key factors, potential external influences, and assumptions helps analysts understand to what extent the data and insights can be useful and trustworthy.

Make sure to take note if there are any activities conducted that might have a significant influence on the respondents’ answers or the number of responses submitted. For example, in the 2nd week of the collection period in Legazpi City, the Mayor attended a major conference and encouraged citizens to answer the survey during his remarks, which spiked the number of participants answering the survey at that date and time. Being aware of these activities helps differentiate legitimate spikes in the number of respondents (as in the example above) versus potentially malicious activity (trolls or bots), or an attempt to manipulate the survey results.

Getting the People Involved

To get quality responses, LGUs need a dissemination plan that makes good use of existing resources. It’s important to consider the following when creating the plan:

- Consider using ONLINE and in-person platforms to make the survey more accessible.

- Keep the questionnaire short — respondents will be more likely to leave questions unanswered if the survey has multiple pages.

- Clearly describe the topic so respondents understand what is being talked about

- Make sure the survey is easy to fill out or use step-by-step instructions so your respondents understand how to fill it out

- Consider using survey incentives (such as load cards, or prizes – the Legazpi assembly provided gift coupons to Jollibee to participants) to motivate respondents to take your survey.

- Thank the respondents for participating and let them know that you have read their feedback and have taken it into account.

If you are struggling to get a response from a particular demographic group, you might supplement random sampling with more targeted recruitment in partnership with ‘community ambassadors’ who are trusted by that community.

In the Legazpi Citizen Assembly, the LGU enlisted the aid of Fr. Jose Victor “Jovic” E. Lobrigo, President and CEO, SEDP (Simbag sa Pag-asenso, Inc.), and Rosemarie Quinto-Rey, President of the Albay Chamber of Commerce and Industry to ensure that the government heard from the small businesses that they wanted to support. SEDP works with micro and small businesses in Legazpi and the Albay Chamber had members that fell within the small business category as well. By approaching community leaders, the feedback collection was able to reach the target community of this assembly.

Ensuring Inclusivity

One of the biggest challenges in collecting citizen feedback is ensuring that sectors are well-represented and that a sufficient number of responses are collected to adequately represent the entire population. Below are recommended practices to ensure inclusivity in collecting citizen feedback.

Table 2: Challenges and Possible Solutions

| Challenges | Possible Solutions |

|---|---|

| Access to digital technology | Enable creation and deployment of accessible ICT content e.g., by providing free internet hotspots, improving network signals, etc. The LGU may also partner with National Government Agencies and other stakeholders in arranging for improved access to the internet and digital devices. In parallel, the LGU may deploy additional alternative means of collecting citizen feedback (e.g., off-line and non-digital collection tools). |

| Cost and Affordability of ICT | Provide free and accessible internet connection and/or ICT facilities for the constituents. Work with the private sector for affordable solutions. |

| Lack of understanding of the technology | Adopt or create citizen-oriented/user-friendly digital tools and deploy understandable ICT content. Reach out to local technology champions, advocates, and experts. The local Academe is a good candidate for collaboration. |

| Lack of trust in the technology | Promote the technology in a non-discriminatory manner and increase transparency in decision-making or budget spending. |

| Poor technical assistance | Assign qualified individuals (e.g., appoint a Digital Democracy Officer) to assist and coordinate with the local ICT council and/or Academia for collaboration. |

| Security and Privacy | Harmonize government regulations and reach a consensus in the implementation of a basic kit of interconnected and interoperable electronic services. Follow industry-prescribed security best practices. |

Be creative in approaching the challenges. In Legazpi City, the small business owners went to SEDP centers (SEDP is an NGO that works with micro and small businesses) and filled in the online survey using the SEDP internet. In some cities, the barangay halls were willing to provide WIFI hotspots to allow the communities to use their internet connection. MBC also reached out to the private sector to request the use of the WIFI in their retail locations. It is recommended that the team identify areas where ICT infrastructure can be accessed by the communities - to make it easier for citizens to join the conversation.

Communications Channels

Promoting the survey through various communications channels is essential to get a larger response to the survey. MBC recommends using different communications channels – such as Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, etc. as well as using the local language when promoting the survey. In Iligan City, all promotional material was produced in both English and Cebuano, while in Legazpi City, the citizen assemblies were held in Filipino.

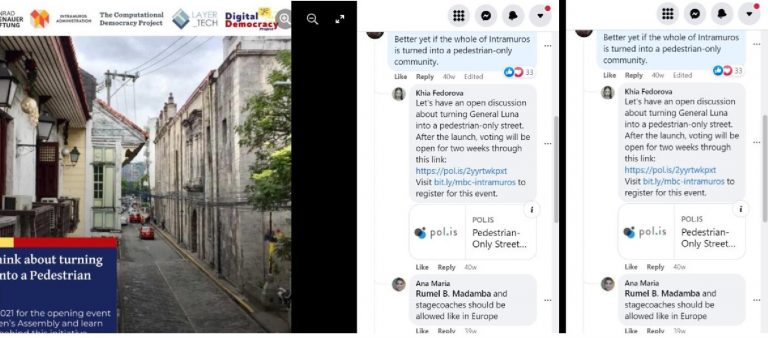

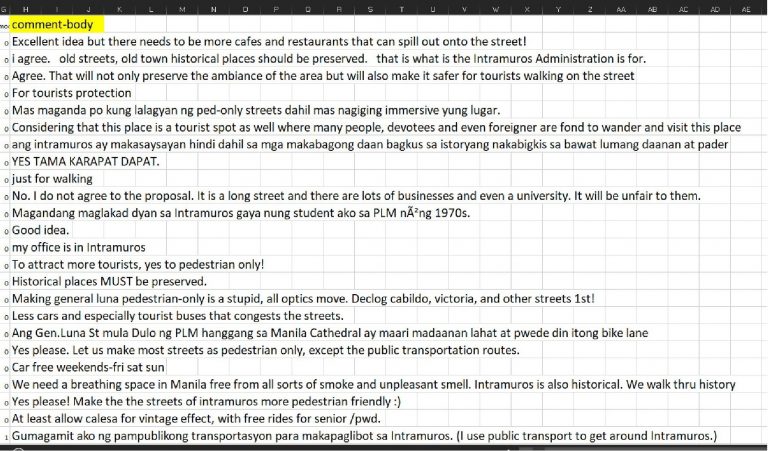

The channel or website used can also determine the tone of feedback received. During the Digital Democracy run in Intramuros in 2021, a total of 1014 respondents submitted their votes via Pol.Is, and a total of 433 qualitative comments were scraped from Facebook and Pol.is’ open message box.

The report from Layertech Labs on the data gathered during the Intramuros run observed that :

● Suggestions are more extreme on Facebook compared to Pol.Is qualitative comments. (e.g. Facebook comments would recommend closing entire Intramuros to motorized vehicles versus Pol.Is responses that recommend the closure of specific roads only.)

● Comments in Pol.Is are more detailed especially when it comes to disagreements and concerns regarding the policy. (e.g. Facebook comments would express frustration without specific policy recommendations)

● While social media provides a wealth of feedback data from stakeholders, it may not necessarily represent all sectors.

● Some respondents may also be hesitant to voice out concerns publicly (on Facebook) while concerns and disagreement with the policy are more voiced out via Pol.Is.

Below are screenshots of comments received from Facebook, compared to the comments received from Pol.is

Facebook Comment Screenshots

Comments from Pol.Is

Consider crafting a press release to share with the media to encourage more participation from citizens. It is also important to coordinate with the LGU’s communications officer ahead of time regarding posting the survey on the LGU’s social media pages. When the survey is posted on the LGU’s social media, citizens tend to participate more, because of the LGUs’ credibility and responsibility to release verified content.

During the Digital Democracy run in Intramuros, many articles were published by the mass media that spread the word about the Intramuros survey and encouraged participation in the assembly. This yielded participation from more than 1000 voters on the issue, as compared to an average of 400 participants in the other surveys.

Sample Articles on “Pedestrian Only Streets in Heneral Luna” - 2021 Digital Democracy Run:

Collecting and Analyzing Data

Be prepared to process huge amounts of data — depending on the survey respondents, up to hundreds to thousands of rows of feedback. For this, it is essential that data processing tools and software be used. Some data analyzing tools will be presented in Section 6 below. Annex 2 provides information on the data mining process, and how to determine the sample size needed.

It is also important to assign the data pre-processing and processing task to a person or a partner institution capable of analyzing and interpreting the data.

If the LGU does not have an in-house staff who can handle the analysis, you may reach out to other national government agencies (e.g. DICT, DOST), the private sector, or the local academia for assistance. During the Digital Democracy initiatives in 2021, MBC partnered with Layertech Labs, a data analysis organization, to provide a detailed analysis of the data collected. It is best to reach out early, and have the partner institutions review the survey questions before it is launched.

The analysis framework and methods that will be used will depend mostly on (1) the size and profile of the data available, and (ii) the key information requirements of the initiating government office. Normally, analysts may do either of the two methods described below, or both:

Descriptive Analysis

- Describes, summarizes, and presents data collected in a manner relevant to the context. For example, the government may want to see if the respondents are in favor of closing a major street in the locality, and what are the respective demographic profiles of those who agreed and disagreed. The pilot cases in the Digital Democracy process are mostly cases of Descriptive Analysis.

Predictive Analysis

- Makes predictions and models based on data. Examples of actual uses of predictive analysis in government offices include predicting potential bottlenecks in a business process, predicting the ‘classification’ or policy position of a certain person depending on his/her demographic profile.

Data Protection and Privacy

Risks to data protection and privacy of data in both traditional and digital formats may be assessed by data protection legislation and data protection training. Risk assessment is also beneficial in terms of user awareness — how data and information are gathered, treated, processed, and a general understanding of how digital technologies can influence the manner in which information is received and imparted, influencing how people form opinions. Some tips on data handling based on the Data Privacy Act of 2012 can be found in Annex 1.

Visualization and Presentation of Results

- Support survey results with related data for an additional layer of analysis. For example, if the survey topic is all about the closure of certain roads to motorized vehicles, it would be helpful to supplement feedback data with relevant trafficrelated data for a more holistic analysis. Annex 3 provides additional sources of data for analysis.

- Use graphs, flowcharts, and infographics to present results in a clear, simple, and easily understood format by stakeholders. Visualization tools are presented in Section 6.

Step 5: Conducting a Closing Citizen Assembly

After the results are analyzed and visualized, it is recommended that the LGU conduct a closing citizen assembly to present the results of the survey and analysis. Similar to the opening citizen assembly, invite key stakeholders and participants, and use the data collected and analysis results to drive further discussion.

Together with the stakeholders, come up with proposed solutions to the concerns raised, and suggested next steps to move forward. Understanding the reasons behind voters’ disagreement with a policy is a crucial first step in addressing key concerns and getting them to support the policy later on.

Recommendations should be listed down in a report

Make sure that the rationale, the process, and the key findings are clearly outlined in a report. We recommend writing this in the participants’ language so survey participants can review the results, or directly participate in the writing of the report itself.

Some things that need to be considered:

- Consider releasing the assembly’s final report with a short executive summary in multiple formats (e.g., mobile-responsive web pages, e-books, etc.) to make it accessible.

- Consider arranging an informal session between LGU officials and assembly participants (or key personnel related to the policy topic) to enable a more indepth discussion on the findings, interpretation of results, and stakeholder suggestions.

- The final recommendations should be formally passed over to the decisionmaking body in the government (e.g. in LGUs, this would be the Mayor’s Office). It’s best if this handover is led by a group of assembly participants who can also discuss their experience and explain the assembly’s decisions.

- Consider the need for a trial run. Submit reports to decision-makers or local stakeholder groups for feedback before they are finalized and published. The assembly can test the popularity and feasibility of the recommendations and perhaps decide to make some tweaks before they are finalized.

- Consider sharing the report on an online platform to encourage researchers to build on the results.

During the closing event of the Digital Democracy initiative in Intramuros, the survey results were presented to the participants, which showed support for turning Heneral Luna into a pedestrian-only street, while expressing concerns about accessibility, parking, road safety and flooding. Participants in the event took this opportunity to share recommendations with the government for smoother implementation of pedestrianization, such as a special wedding kalesa (horse-drawn carriage) for marriages in San Agustin Church, adding symbols on pedicabs to identify them as official licensed pedicabs to avoid over-charging, and allowing motor vehicles to enter at specific times of the day to accomplish necessary activities for the businesses running in that area.

Step 6: Closing the Feedback Loop

An effective feedback cycle involves closing the feedback loop. This means that there is observable action taken as a result of the consultation. Closing the feedback loop encourages constituents and stakeholders to actively participate in the Digital Democracy process and cooperate with their LGUs.

It is recommended that the LGU post updates on actions taken as a result of the consultation process. Leverage social media platforms and digital repositories to communicate to stakeholders that their LGU is taking their feedback seriously, and is willing to work hand-in-hand with their constituents in community building.

Processing the Policies

- Consider existing policies that may need to be revised to reflect the feedback results. For example, if the community requests more parking spaces in a certain area, check if there is an existing ordinance that grants parking spaces in that area.

- Consider when the next LGU planning session will be held. Schedule the Digital Democracy process so that the report can be used in the planning session.

- Sometimes more awareness of existing policies will suffice – policies and programs may already exist that need to be better communicated with the community. For example, MSMEs may request for training and support from their local governments that are already being offered by the government.

- Consider making modifications to existing local policies instead of enacting new ones.

- Finally, if a new policy is to be made, the results of the citizen feedback analysis may be used as a basis to inform its creation and implementation.

After the Digital Democracy run in Intramuros, in July 2021, the report generated for the project was presented by the administration to the Board of Intramuros. The data collected and insights generated from the Digital Democracy run served as evidence-based data points to discuss the policies surrounding the proposed pedestrianization of Heneral Luna.

Legazpi City has also used the recommendations from the survey to engage with small businesses in their area, to provide training and other support, while Pasig City is still currently considering low-speed streets, and will be using the survey data when they prepare the proposal regarding this topic.

Agenda Setting

With the help of data-centric conversations, stakeholders can get the government to consider their emerging issues and concerns. They can better convince the government to prioritize certain concerns if backed by data and data-driven insights.

For example, stakeholders may lobby for:

- The creation of local policies to address their concerns or consider their suggestions.

- The formal enactment of policy instruments based on data-backed consultations with stakeholders.

- The implementation and translation of policy into programs, projects, and activities– and assessment of the effectiveness of these policies.

With data-backed suggestions, insights, and conversations, the coordination between governments and stakeholders may improve, as they will have a clear set of indicators to monitor.

It’s vital to communicate the timeline of decision-making and key milestones to the community. Send out regular updates via social and local media and email. It’s also essential to keep reporting back to participants over time, especially when the question specifies a long-term timeframe. Citizens will be encouraged to participate and cooperate with their governments if they can see that their feedback is being used to make visible improvements.

Considering Next Steps

It is recommended to meet the team and stakeholders again after some time. Ask the stakeholders if their issues or concerns have been addressed. What other concerns do they have in their locality? Reflect on the process and look for ways on how citizens and governments can keep working together to co-create solutions to the challenges of the locality.

During the Pasig Digital Democracy run in 2021 on the enforcement of Low-Speed Streets, issues about parking and parked cars blocking streets were also discussed during the citizen assembly. Although these issues raised weren’t related to the topic of slower speed limits, the consultation surfaced other issues that the LGU can address, and is a possible issue that can be addressed with another Digital Democracy run.

5. Creating an Action Plan

Action plans help communicate objectives and strategies to different actors in a concise way. Having an action plan[3] helps conduct a seamless Digital Democracy process, getting all stakeholders on the same page as they go through the process. Below is a sample action plan for a Digital Democracy consultation.

Table 3: Example of Digital Democracy Action Plan Template

| Objectives | Tasks | Resources | Outputs | Timeline |

| Plan for consultation | ||||

| Create questionnaire | ||||

| Collect Feedback | ||||

| Analyze Results | ||||

| Present Results | ||||

| Close feedback Loop |

List down the key objectives of the consultation. Under each objective, list down specific tasks and projected resources needed to carry out each task. For each task, identify outputs and target timeline for completion.

Guide questions:

- What is the key policy/program to be discussed?

- When are they to be initiated?

- Who are the authorities and stakeholders involved?

- Who has overall responsibility?

- What are the goals and objectives to be achieved?

- What are the platforms/websites to be used?

- Who is the target audience?

- What supporting measures and policies are required?

- What resources are available?

- What is a realistic timetable to be met?

- What are the challenges, opportunities, and achievements to be realized?

Some useful guidelines on sourcing technical solutions (from the European Committee on Democracy and Governance (CDDG)) can be found in Annex 4.

6. Summary of Tools

Table 4 shows a summary of the tools used in the Digital Democracy process and MBC’s recommendations based on its experience with the project from 2020-2021.

Table 4: A Summary of Tools Used in the Digital Democracy Process

| Spreadsheets | Allow users to store and manage data in a tabular form to be easily visualized and analyzed. | ||

| Product Name | Internet Needed? | Paid or Free? | Usefulness / Tasks Accomplished |

| MS Excel | No | Paid | The Digital Democracy team used these software programs to organize participants’ data, and responses received, and categorize participants. |

| Google Sheets | Yes | Freemium | |

| OpenOffice Calc | No | Free | A number of academic partners of Layertech used open-source tools like OpenOffice Calc to collect, organize, and calculate summary statistics of data collected. 4 |

| Video-conferencing Tools | Enable people to communicate and collaborate online, remotely. Requires a personal computer, laptop or smartphone, web camera, microphone, and a stable internet connection. | ||

| Product Name | Internet Needed? | Paid or Free? | Usefulness / Tasks Accomplished |

| Zoom | Yes | Paid | The Digital Democracy citizen assemblies were held through zoom. Participants were placed in breakout rooms to provide recommendations to the government in the closing assembly. |

| Other tools: | Google Meet, Skype, and MS Teams are other available conferencing tools online. | ||

| Web Portals | A website that specifically caters to a defined audience and allows for user input and interaction, and may restrict certain functionality to a group of users only. | ||

| Product Name | Internet Needed? | Paid or Free? | Usefulness / Tasks Accomplished |

| Local Government or Government Agency Official Websites | Yes | Can be provided by DICT | Posting the Digital Democracy activities and updates on the LGU’s official website provides legitimacy to the process. LGU web portals can also be used to collect data, determine issues, and provide solutions. |

| CloudCT5 | Yes | Free | Offers hosting and basic analytics and reports for partner LGUs. Helps LGUs collect and analyze citizen feedback data, and incorporate findings in decision and policymaking. |

| Other Tools: | Live Chat and Chatbots are features of portals that allow for quick feedback collection. | ||

| Polls and other Survey Platforms | Offer online survey services that LGUs can use to collect citizen feedback. LGUs can create survey questionnaires or voting polls, and deploy them online for collection. | ||

| Product Name | Internet Needed? | Paid or Free? | Usefulness / Tasks Accomplished |

| Pol.Is | Yes | Free | The Digital democracy project from 20202021 used Pol.Is to gather real-time data from citizens. It uses AI for analysis and visualization of data. |

| Slido | Yes | Freemium | This was used in the digital democracy citizen assemblies to crowdsource top questions and get instant feedback through online polls. |

| Google Forms | Yes | Freemium | Google Forms is convenient for organizers and familiar to many participants. However it appears many participants in our first Pasig project (2020) dropped off after they were asked to fill one. We have learned this was because they did not want to provide personally identifiable information. The succeeding digital democracy processes removed the google form requirement. |

| Social Media | Social media platforms may be leveraged by LGUs to actively interact with their constituents, coordinate Digital Democracy processes, disseminate Digital Democracy related initiatives and raise awareness on the current projects and initiatives of the LGU. | ||

| Product Name | Internet Needed? | Paid or Free? | Usefulness / Tasks Accomplished |

| Viber | Yes | Free | The project team members used Viber and Messenger groups to coordinate with the LGU teams. |

| Messenger | Yes | Free | |

| Yes | Free unless the LGU uses paid ads. | Used to disseminate Digital Democracy related initiatives and raise awareness on the current projects and initiatives of the LGU. | |

| Yes | |||

| Yes | |||

| SMS (Text Messages) | No | Paid | The Digital Democracy team sent text blasts to stakeholders to invite participants to answer the survey and join the citizen assemblies. |

| Data Processing and Visualization | Data is extremely powerful in driving conversations in the Digital Democracy process. Data provides evidence-based arguments and a basis for decision and policy-making. The feedback data collected, along with available data housed by the LGU, can be processed, visualized, and analyzed, to gain key insights. | ||

| Product Name | Internet Needed? | Paid or Free? | Usefulness / Tasks Accomplished |

| R | No (But internet is needed for downloading packages) | Free | A programming language that may be used to collect, process, and visualize data. Requires technical, programming, and mathematical competencies. |

| Python | Free | ||

| Tableau6 | Yes | Free | A data visualization software that can be used to generate a wide variety of graphs and custom analytics dashboards. |

| No | Paid | ||

| Google Charts | Yes | Freemium | An easy-to-use online tool under the Google suite, which allows users to generate basic charts for visualization. |

[4] Some researchers advocate for the use of open-sourced software. OpenOffice Calc is an open sourced software that is free, and isn’t vendor-locked like many popular software.

[5] CloudCT is an online portal developed by Layertech Labs, with the help of partners from the Local Government, the Academia, and Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) to help LGUs collect and analyze citizen feedback data, and incorporate findings in decision and policy-making. The tool hosts various tools, technical guides, studies, and reports on how LGUs can leverage feedback data for streamlining and decision-making. (Accessible via: www.CloudCT.tech) Digital Democracy reports in the 2021 run are available and downloadable for FREE in the CloudCT platform.

[6] Tableau offers a free public version, which can only be used online. Users may avail of Tableau’s paid services to enable offline use of tools, and premium features.

7. Conclusion

The Digital Democracy process provides an online avenue for governments to gain input from citizens. To be clear, Digital Democracy initiatives DO NOT intend to replace face-to-face consultation. Instead, it aims to supplement and strengthen the consultation process by leveraging digital tools. This proved to be especially useful when the COVID-19 pandemic greatly limited mobility.

The process described in this document may be replicated and built on, by other local government units and institutions for various decision-making cases.

The succeeding handbooks of the Digital Democracy Series provide further detail on Digital Democracy concepts and strategies to embed the process in government decision-making.

Annex 1: Data Privacy Act of 2012

Republic Act 10173 is also known as the Data Privacy Act of 2012.

“It is the policy of the State to PROTECT THE FUNDAMENTAL HUMAN RIGHT OF PRIVACY, of communication while ensuring free flow of information to promote innovation and growth. The state recognizes the vital role of information and communications technology in nation-building and its inherent obligation to ensure that personal information in information and communications systems in the government and in the private sector are secured and protected.”

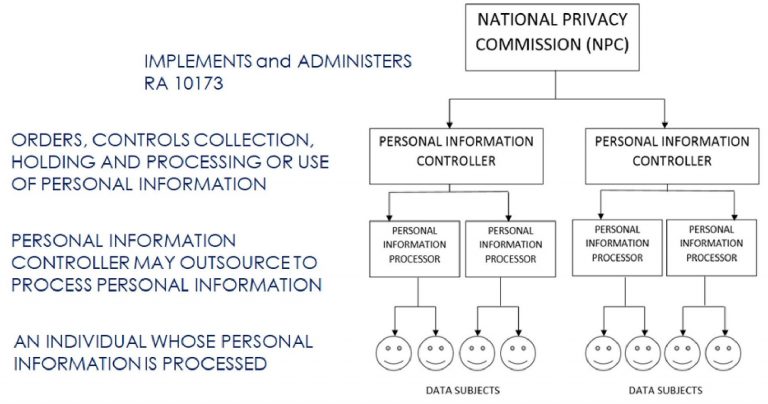

Figure 3 shows a schematic of the Data Privacy landscape in the Philippines.

The Landscape

Figure 3: The Data Privacy Landscape in the Philippines

The Scope

“This Act applies to the processing of ALL TYPES OF PERSONAL INFORMATION and to any natural and juridical person involved in personal information processing INCLUDING those personal information controllers and processors who, although not found or established in the Philippines, use equipment that are located in the Philippines, or those who maintain an office, branch or agency in the Philippines subject to the immediately succeeding paragraph: Provided, That the requirements of Section 5 (Protection Afforded to Journalists and Their Sources) are complied with.”

Citizen Feedback Data Collection Best Practices (in Line with RA10173)

- CONSENT is key! When collecting citizen feedback, especially if it includes the possibility of collecting personal information, provide a privacy note or a privacy policy statement. Have the respondent explicitly agree to share their data (e.g. an introductory statement on an online survey form, an ‘I agree’ button, or a verbal statement at the beginning of a Zoom meeting).

- Do not collect personal information of participants that are not relevant to the issue. Collect only the data that is needed for the analysis. Make sure that every data point collected is mapped to the survey objectives.

- Do not store collected personal information beyond the declared time of use in the privacy statement. Once the data is used to achieve the survey goal, properly dispose of the data according to data disposal guidelines of RA101737.

- Do not share personal data with a third party unless explicitly given permission by the data subject.

- Do not use the collected personal data for purposes other than the declared use.

- Exercise caution when handling the data. Use industry-standard digital security tools and measures to protect the data. (e.g. do not store data in insecure and unencrypted repositories)

7 The IRR states “Personal data shall be disposed or discarded in a secure manner that would prevent further processing, unauthorized access, or disclosure to any other party or the public, or prejudice the interests of the data subjects.” Source.

Some general best practices include: (1) have a formal and documented process for data destruction within the organization. Who is disposing of the data and how was it disposed of? (2) Shred papers and documents with sensitive information before disposing and (3) destroy CDs/DVDs and any optical disks by pulverizing, cross-cut shredding or the like. Here is a US document from US Dept. of Education with full guidelines on proper data disposal.

Annex 2: Principles of Data Collection

Sampling

Sampling is the process of selecting individuals from a total affected population. Selected individuals should represent the larger population and reduce the time and cost of data collection. Generalizations about the total population can be extrapolated from the results of the sample survey if the sample is representative.

Make sure to inspect the demography of the respondents. “Are we collecting enough samples from the target sectors?”

Sampling Frame

A sampling frame represents a population that the sampling process is intended to cover (e.g., a region within a country, a group of displaced people, etc.) It is defined at the start of the assessment planning process.

The Ideal Sample Size?

In statistics, the ideal sample size will depend on your population size (the total number of people in the group), the margin of error (smaller margin of error, the more reflective your result is with the population), and the confidence level (how confident you are that the population will answer within the range you identified).

There are various online tools that can be used to calculate the ideal sample size for your survey.

Annex 3: Using Open Data

It’s important to use reliable external data if there is a plan to explore more advanced analysis, apart from data collected within the LGU. Depending on the type of data needed, there are different places to go. Here are some of the resources to be explored:

From science and research to manufacturing and climate, data.gov is one of the most comprehensive data sources around the globe. Datasets are available in typical formats such as CSV, JSON, and XML. Metadata is frequently updated as well, giving the user complete transparency and clarity. This site is well-suited for exploring government and global data.

In 2014, the Philippines launched the data.gov.ph open data portal as a central resource for government datasets.

This is one of the most frequently updated and complete open data sources for information on GDP rates, logistics, global energy consumption, disbursement and management of global funds, and much more. There are even visualization tools for some datasets. This site is well-suited for exploring financial and economic data.

The Philippine Government E-Procurement System (PhilGEPS) is the primary and definitive source of information on Philippine government procurement. The official PhilGEPS website hosts an open data portal wherein the public can download datasets on all the procurement transactions of all government entities in the Philippines.

The Electronic Freedom of Information (eFOI) portal is a government information portal wherein users can request specific data from national government agencies and LGUs in the Philippines. The eFOI portal also allows public download of previously granted data requests, as well as an information repository categorized by sector.

Annex 4: Guidelines in Sourcing Technical Solutions - European Committee on Democracy and Governance (CDDG)

The European Committee on Democracy and Governance (CDDG) shares the following guidelines on sourcing of technical solutions and software for Digital Democracy Projects:

- Make sure that there is sufficient technical knowledge for the evaluation of possible need for adopting new hardware and/or software.

- Use technical platforms and solutions that meet the requirements of both the project objectives and the target audience.

- Identify whether electronic identification or electronic signatures are required for authentication.

- Identify possible technical assistance requests from stakeholders.

- Recognize the need for cooperation between ICT experts and persons with knowledge of participatory processes.

- Give preference to standardization of Digital Democracy solutions.

- Consider the flexibility of services and avoid vendor lock-in.

- Ensure that the Terms of Service (or Service Level Agreements) meet policy and legal requirements, and in terms of human rights.

Acknowledgments

- Frei Sangil

- Data Scientist, Layertech Software Labs

- Engr. Lenidy Mañago

- Research Specialist, Mañago Engineering Consultancy

- Lany Laguna-Maceda, DIT

- Associate Professor, Bicol University College of Science

- Administrator (Atty.) Guiller Asido

- Administrator, Intramuros Administration

- Rodrigo S. Magat

- Consultant and Board Secretary

- Intramuros Administration

- Fr. Jose Victor E. Lobrigo

- President and CEO, SEDP (Simbag sa Pagasenso, Inc.)

- Carlos “Chito” Ante

- City Administrator, Legazpi City

- Rosemarie Quinto-Rey

- President, Albay Chamber of Commerce and Industry

- Honelet Soreda-Bertis

- Legal Officer/Secretary General, Albay Chamber of Commerce and Industry

- Michael Lagcao

- Office of the Vice Mayor, Iligan City

- Karen May Crisostomo

- Pasig Transport Office

- Ms. Czarina Medina-Guce

- Governance Specialist, UNDP, and Lecturer at Ateneo de Manila University

- Luz G. Galda

- OIC – Division Chief, Business Development Division, DTI – Lanao del Norte

- Ma. Welissa V. Domingo

- Head, SME Development Unit, DTI – Lanao del Norte

Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International

The contents of this material can be used in any way permitted by the copyright and related legislation that applies to the intended use. No permission is required from the rights-holders for non-commercial use. However, attribution is required for the modification and dissemination of this handbook and its contents.

Please credit and/or link to Makati Business Club.

For more information, concerns, and queries, please contact: MBC Secretariat at makatibusinessclub@mbc.com.ph

The Digital Democracy Project